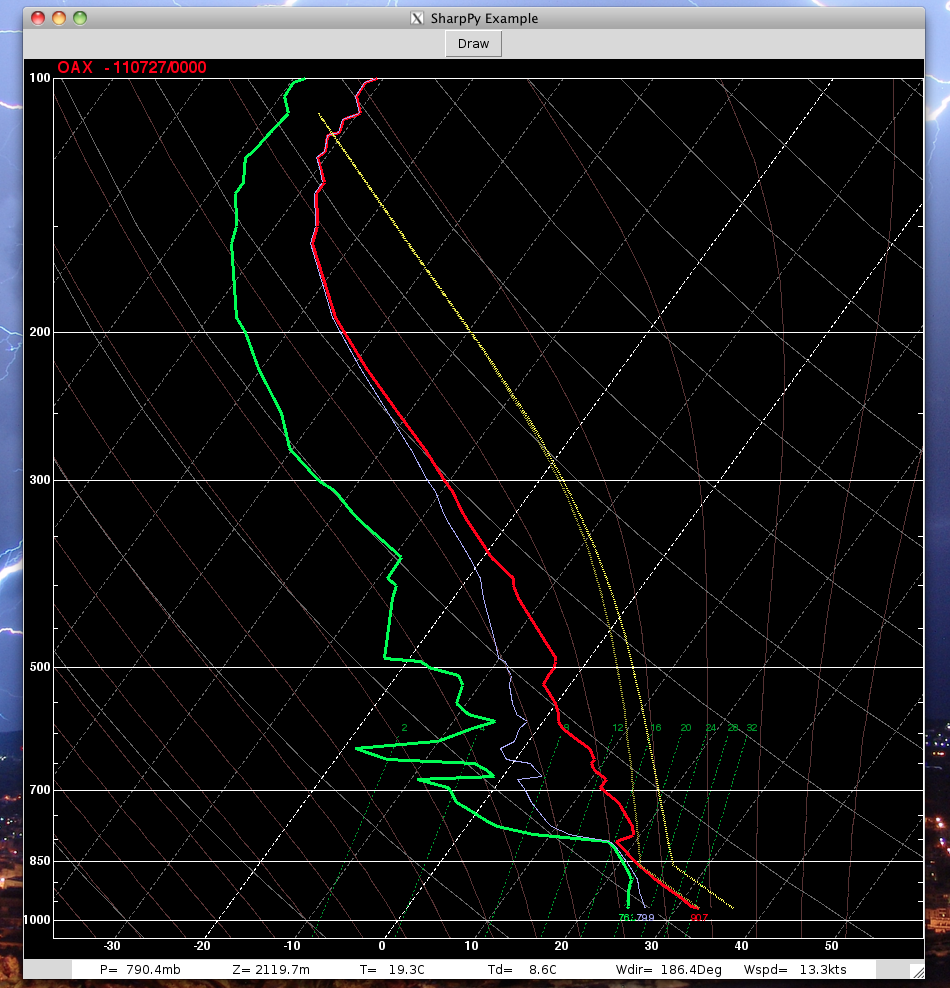

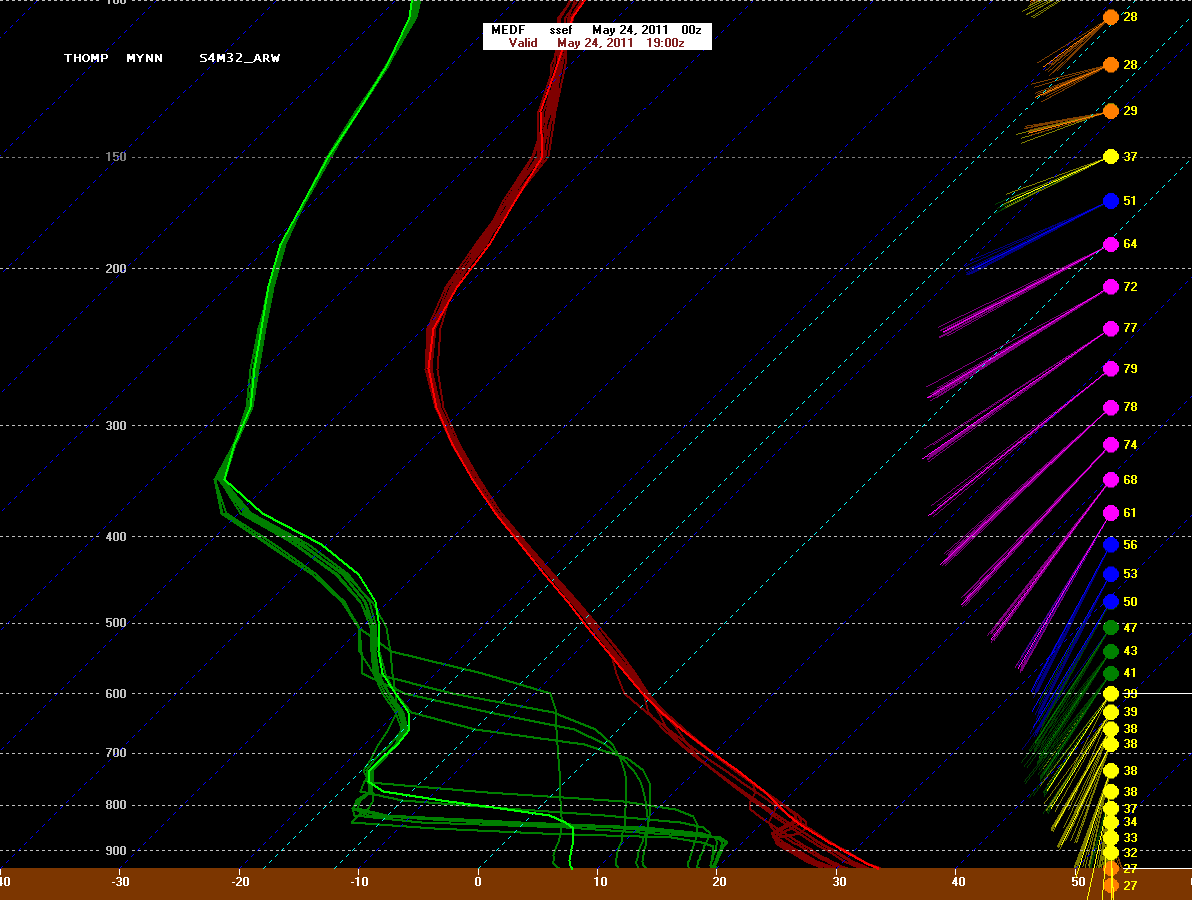

Those who are regular readers of this blog know by now that my research interests are centered on operational meteorology, data visualization, and data mining. For the 2011 Hazardous Weather Testbest (HWT) Experimental Forecast Program (EFP), I was able to combine my interests by creating a means of viewing model forecast soundings from various convection-allowing models, for the same location, simultaneously. Now, I didn’t create the viewing tool, but created a way to properly format millions of lines of data to utilize the BUFKIT sounding program. An example of one of these ensemble soundings is shown below.

As you can see, the ensemble sounding illustrates several different forecast scenarios that are not apparent when looking at a single sounding. In severe weather forecasting, these sometimes subtle differences in an atmospheric profile can lead to vastly different results. By looking at an ensemble of solutions, forecasters can begin to gauge the variability of the numerical guidance, as well as the predictability. Researchers also benefit. In the HWT this year, we learned about how different model physics impact the atmospheric profile, which, in turn, might introduce systematic biases into the forecast. Knowing this allows researchers to develop better ensembles and better models.

As you can see, the ensemble sounding illustrates several different forecast scenarios that are not apparent when looking at a single sounding. In severe weather forecasting, these sometimes subtle differences in an atmospheric profile can lead to vastly different results. By looking at an ensemble of solutions, forecasters can begin to gauge the variability of the numerical guidance, as well as the predictability. Researchers also benefit. In the HWT this year, we learned about how different model physics impact the atmospheric profile, which, in turn, might introduce systematic biases into the forecast. Knowing this allows researchers to develop better ensembles and better models.

Creating this data set was not an easy process. I had to read in text-files containing the sounding information (example located at the end of the post) for each forecast sounding points — 1146 per model — in each of the 18 numerical models. At that point I needed to be able to compute various thermodynamic parameters from the soundings, so I rewrote most of the thermodynamic and kinematic routines in the Storm Prediction Center’s (SPC) sounding viewer, NSHARP (National Skew-T and Hodograph Analysis and Research Program), in Python. This allowed me to compute a thermodynamic and kinematic parameters in a wide variety of ways for the HWT-EFP, all consistent with what Storm Prediction Center forecasters are used to using in operations.

After computing the necessary thermodynamic fields, I then created sounding files in BUFKIT format for each of the 1146 sounding sites for each of the 18 models. Lastly, I combined the 18 model forecasts for each of the 1146 sites into a single file and output 1146 more text files containing the ensemble sounding files which could then be read by E-BUFKIT. A sample image is above. All-in-all this took about 1 hour of computation time on 18 separate computers. That’s a lot of data to crunch through!

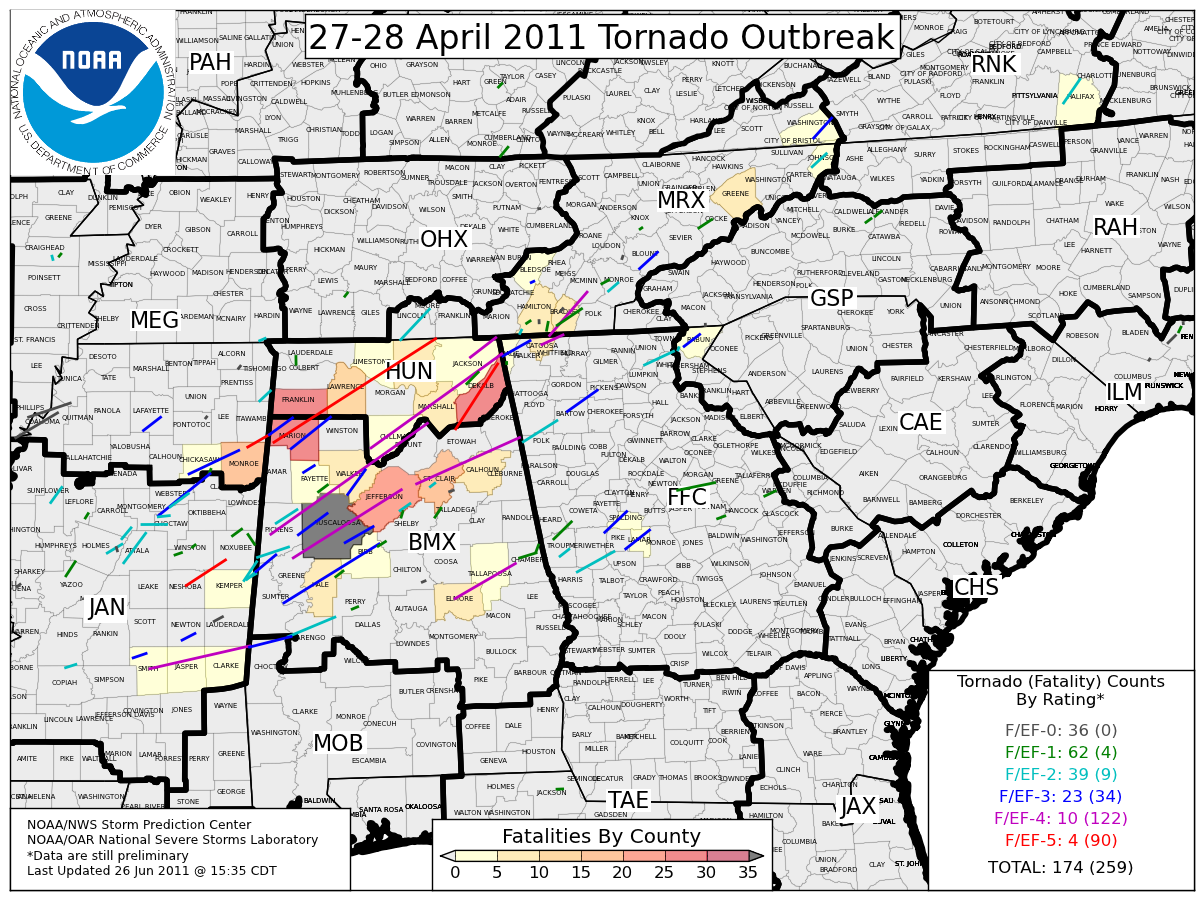

After doing this for the HWT-EFP, I thought to myself, “Why stop there?”. Since the end of the EFP, and with the help of John Hart of the Storm Prediction Center, I have begun work on creating an ensemble sounding viewer — written entirely in Python — based on the SPC’s sounding program (NSHARP). Why Python? Because Python allows the program to be cross-platform, meaning anyone who installs Python on their computer can use the program.

The ultimate goal is to create this program and then release it to the atmospheric community as an open source project. This would allow researchers, forecasters, and hobbyists to be able to use the program to view model soundings in both a deterministic and ensemble framework. Additionally, by having a community supported sounding tool, it is my hope that researchers in the climate community will also use this program for their research. If the meteorology community adopts a single sounding tool, scientists, forecasters, and hobbyists will be able to quickly compare parameters from climate models, weather models, and observational data, knowing that the values were computed in the same manner. This would be a huge boost to comparing historical, current, and future events. Not to mention allow for consistency between datasets.

I’m still in the early stages of development. My hope is to be able to present an alpha version of this program at the American Meteorological Society’s Annual Meeting in New Orleans next January. I’ll have my work cut-out for me…

In the mean time, a screen shot from this new sounding tool is shown below. This prototype supports active read-out, with on-the-fly interpolation as one moves the mouse over the sounding. The read-out is listed at the bottom of the sounding.

I’m interested in knowing what people think, so feel free to leave me feedback!