I am going to begin this post by saying upfront, in bold font.

I merely have a problem with people justifying their chase activities by saying they do it to “help the NWS” or to “save lives”. I have no problem with people who chase, just be honest with why you do it. In fact, since I know I’m going to take a lot of heat from certain groups within the chaser community, I’m going to repeat it.

OK, now that the disclaimer is out of the way, what is the purpose of this post?

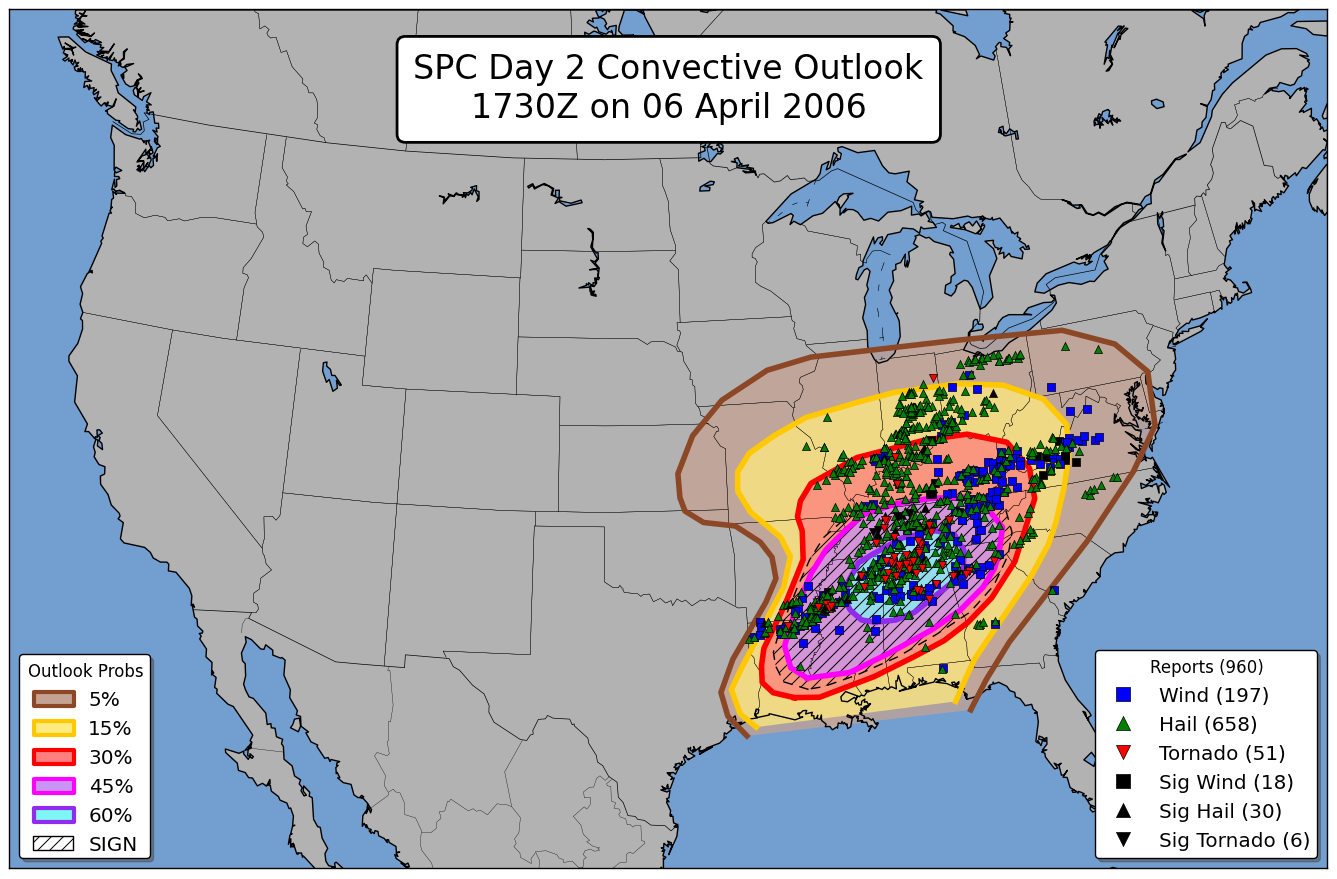

In the wake of last weekend’s tornado outbreak, several news agencies (LA Times, USA Today, and Detroit Free Press just to name a few) have written stories on the (exponential?) increase in the number of storm chasers on the roadways. It is not my intention to discuss the complaints of emergency managers and other local government officials. (That will have to be left for a future post.) Nor do I intend to discuss whether chasing is morally wrong and/or should it be outlawed. Instead, I want to stick to the all-too-often used storm chaser justification for chasing, “Storm chasers save lives.” I’ve seen this justification used in the numerous stories I’ve read this week. I’ve heard storm chasers complain about the “bad rap” they are getting; that people are focusing on the actions of a few and forgetting that “chasers save lives”.

Storm chasing really began to take off in the mid-1990s with the advent of the first Verification of the Origin of Rotation in Tornadoes Experiment (VORTEX) and the subsequent movie Twister. Since these two events, the number of people who identified themselves as chasers has been on the rise (at least according to my perceptions). In recent years, television shows on storm chasing, software such as GRLevel3, ThreatNet, and Spotter Network, as well as the increased cell-phone bandwidth, among many other things, has resulted in what I perceive as an almost exponential growth in the number of storm chasers. If these storm chasers really were chasing to “save lives” as many or most claim, I would hope to see some sort of reflection of this in the fatality counts from tornadoes. After all, more people out saving lives should result in more lives being saved.

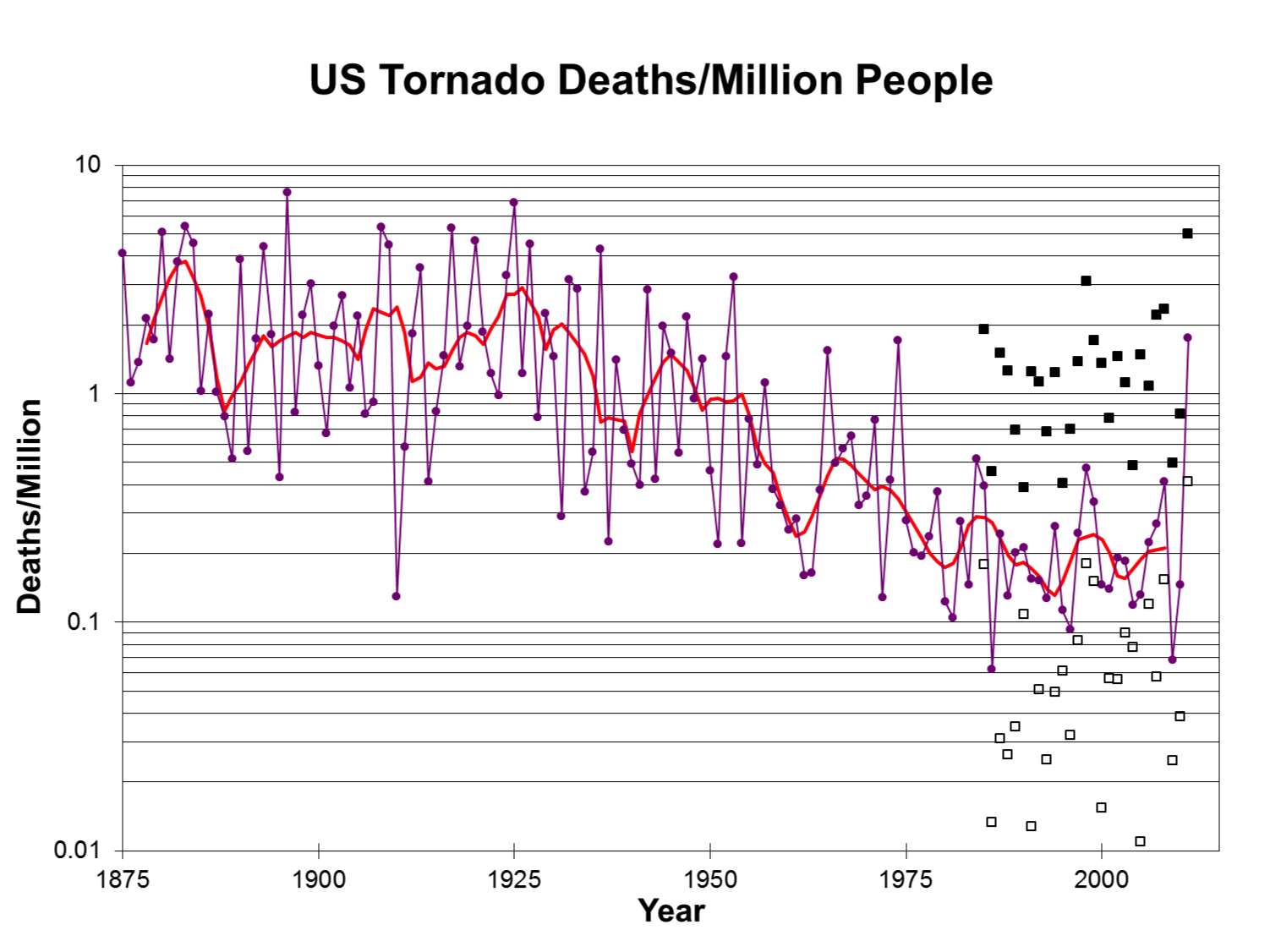

Below is a figure courtesy of Dr. Harold Brooks. It shows the annual number of tornado fatalities in the United States in terms of deaths per million people. Examining tornado fatalities in this context attempts to account for the fact that the population is increasing, and thus there are more people susceptible to losing their life in a tornado.

What should be very obvious is that from about 1950 through about 2000 the trend is decisively downward. However, since around 2000, the trend is approximately flat, meaning that the odds of dying from a tornado is roughly the same now as it was back in 2000. This figure is one of my absolute favorites as it contains a lot of information and leads to a lot of tough questions for the severe weather community. One question that is often asked is, why does the trend seem to flatten out in the 2000s? There could be a lot of reasons why this is, and we’ll leave those to another post. My point here is that with the explosion in the number of chasers, I would expect to see some reflection of this in the number of fatalities resulting from tornadoes. However, the data do not seem to suggest that storm chasers have had that much influence in saving lives.

“But, Patrick, storm chasers provide a valuable service to the National Weather Service by providing real-time information to aid in the warning process. You can’t use a single figure to negate all the contributions of chasers to the warning process!” Fair enough. If chasers do provide a significant impact in the warning process, we should see some reflection of their contributions in the various tornado and tornado warning metrics, so let’s take a look.

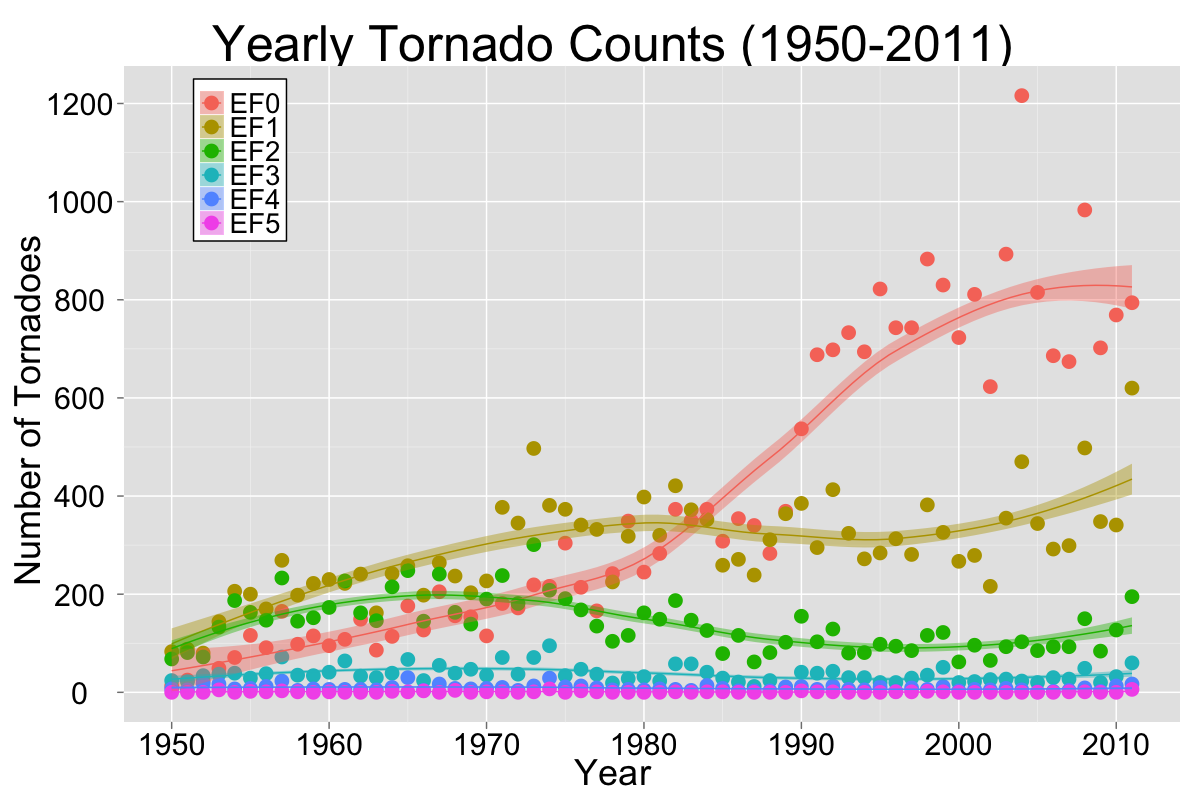

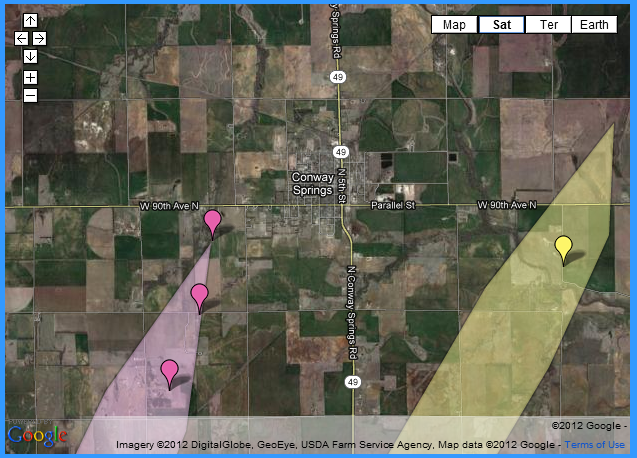

Above is a figure that breaks down the number of reported tornadoes by year and by F/EF rating. As with the figure before it, there is a lot of information behind the data going into this figure, but we’ll leave that for another post as well. For the current purpose, you’ll notice that for the most part, most of the data have remained unchanged. The exception being the number of EF-0 tornadoes, and to a lesser extent the number of EF-1 tornadoes, dramatically increases starting around 1990. This increase coincides with the advent and widespread adoption of Doppler radars. With the increased information Doppler radar provided meteorologists, weaker tornadoes were more easily detected, and thus, the number of reported weaker tornadoes has increased. If chasers had a significant impact in the number of tornadoes observed, I would expect to see some sort of change to the trend-lines beginning in the mid-1990s as the increased number of chasers saw more of the tornadoes that meteorologists missed. The truth is, the impact of chasing is circumstantially less than the impact due to adoption of Doppler radar.

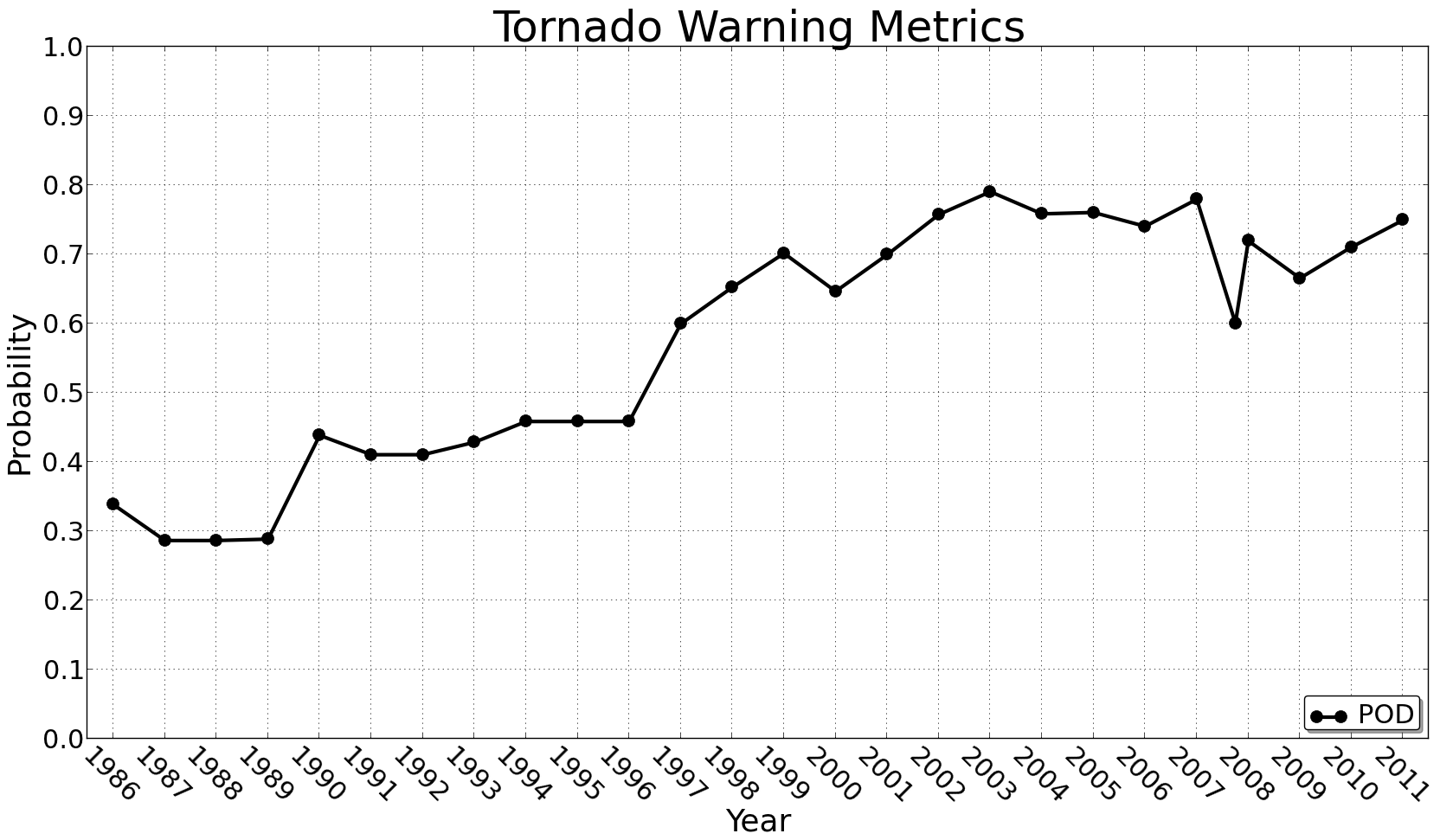

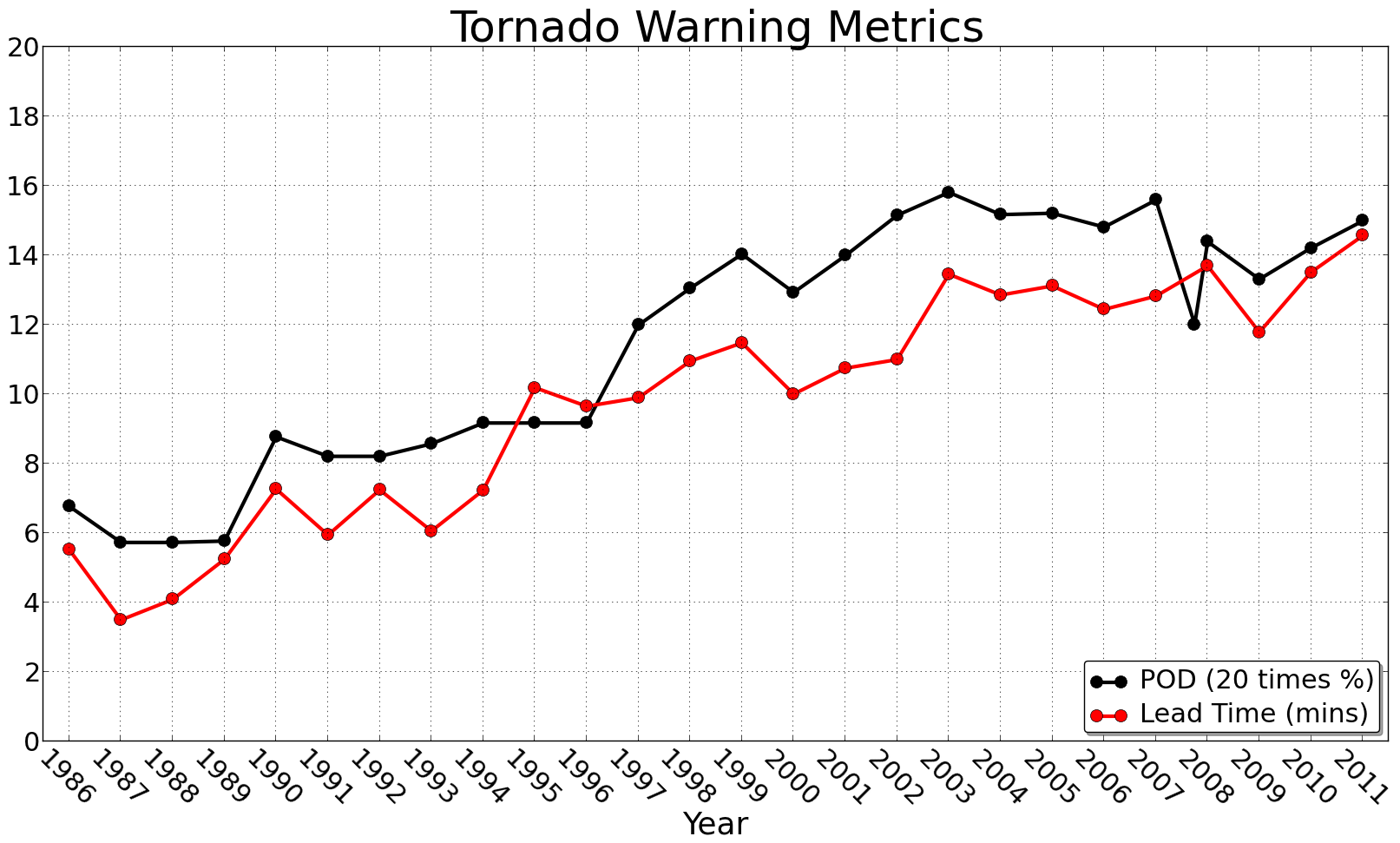

To illustrate this even further, lets consider the probability that a tornado will occur in a tornado warning probability that a tornado that is occurring has been or will be warned. (In verification parlance, this is known as Probability of Detection, or POD.) As the figure below indicates, the Probability of Detection has increased consistently, albeit slowly, since around 1990, which is roughly when the increase in weaker tornadoes began. Taking these two pieces of information together, it would suggest that the Probability of Detection has increased as a result of detecting the weaker (F/EF-0 and F/EF-1) tornadoes, and not the result of chasers making reports.

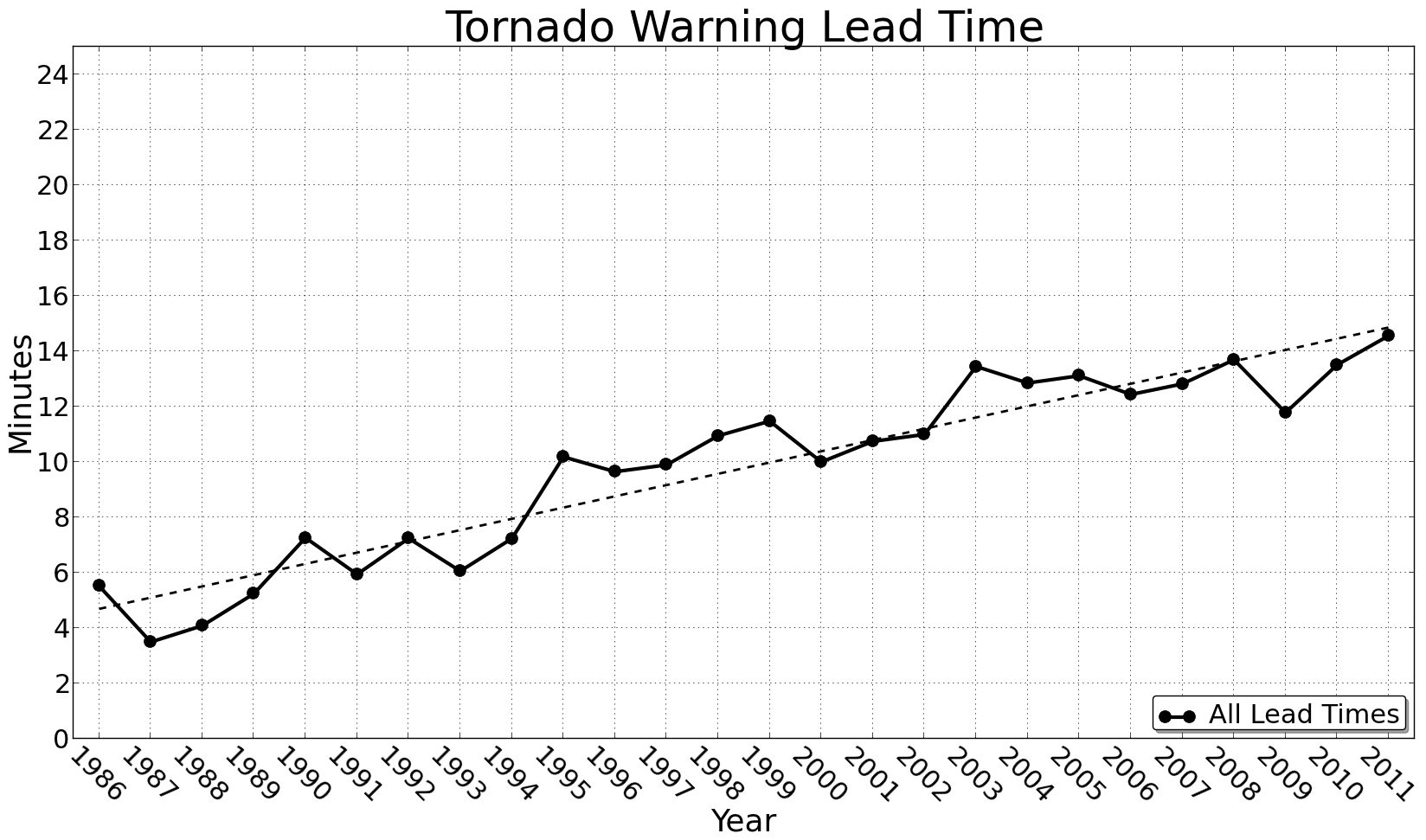

Considering the Probability of Detection aspect of the problem lead me to consider, well maybe chasers have an impact on the tornado warning lead time. With chasers calling in those “rotating wall cloud” reports, maybe the lead time has increased. The mean lead time for all tornado warnings is shown below.

Now, this figure requires a bit of explanation. The National Weather Service defines lead time in a quirky way. First, lead time is merely the amount of time elapsed from the issuance of a tornado warning to the first report of a tornado. Sounds simple enough, right? Well, it gets tricky when you consider a tornado that occurs before a tornado warning. In this case, one would expect a negative lead time. This negative lead time would approach negative infinity in the case that a tornado is never warned. However, this is not how the National Weather Service reports lead time. The NWS assigns a lead time of 0 for all tornadoes that occur before or without the issuance of a tornado. Thus, if you have a low Probability of Detection Thus, if a tornado does not have a warning, or warnings are not issued until after the a tornado is reported, you would expect to have a low lead time because of all the zero lead times that would be averaged in.

What we see in the figure above is that the tornado warning lead time has increased fairly consistently since around 1990. It has increased from about roughly 5 minutes to roughly 15 minutes. Once again, however, this increase in lead time does not appear to be related to storm chasers. In fact, it appears to be directly related to the increase in Probability of Detection.

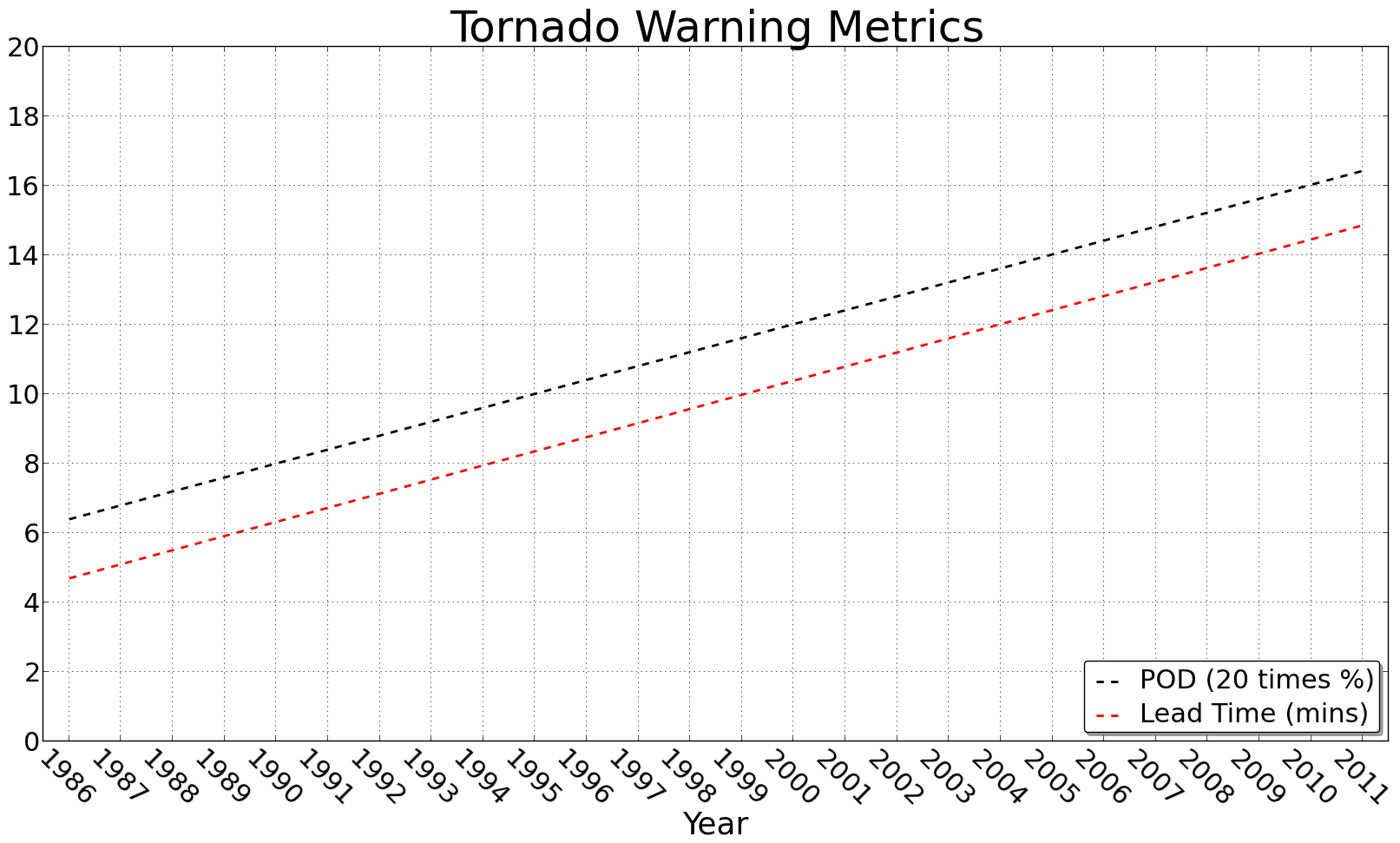

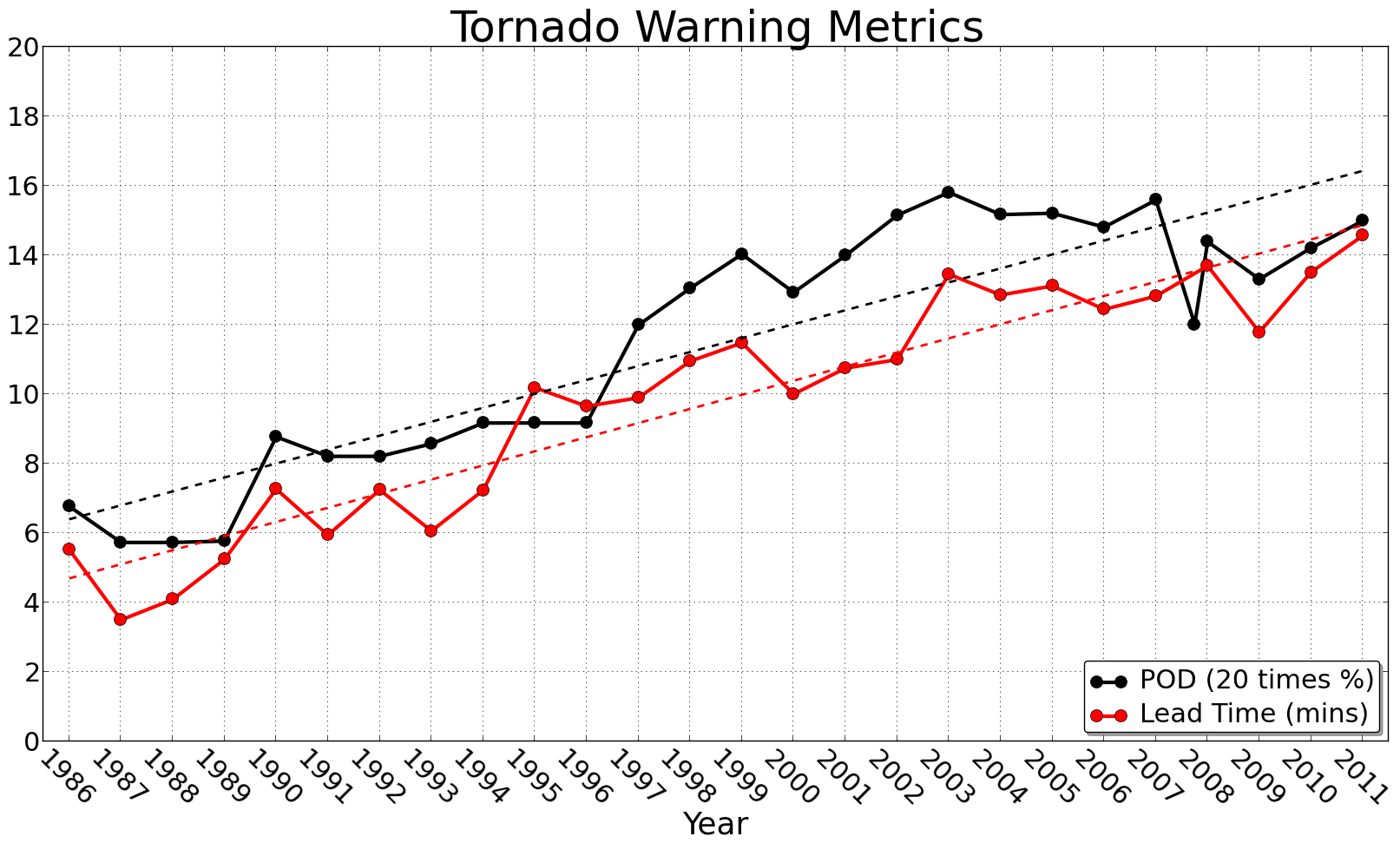

Plotting the Probability of Detection (multiplied by 20) on the same plot as Tornado Warning Lead Time (above), it becomes pretty obvious that the two are highly correlated. In fact, if we were to plot the linear trend lines of the two metrics (below), we would find that the slope is almost the exact same!

For completeness, I’ve plotted both the raw values and the trend lines on the same plot above. Once again, I do not see any significant impact from storm chasers on these metrics. I firmly believe that they are all attributable to better forecaster training and widespread adoption of Doppler Radar.

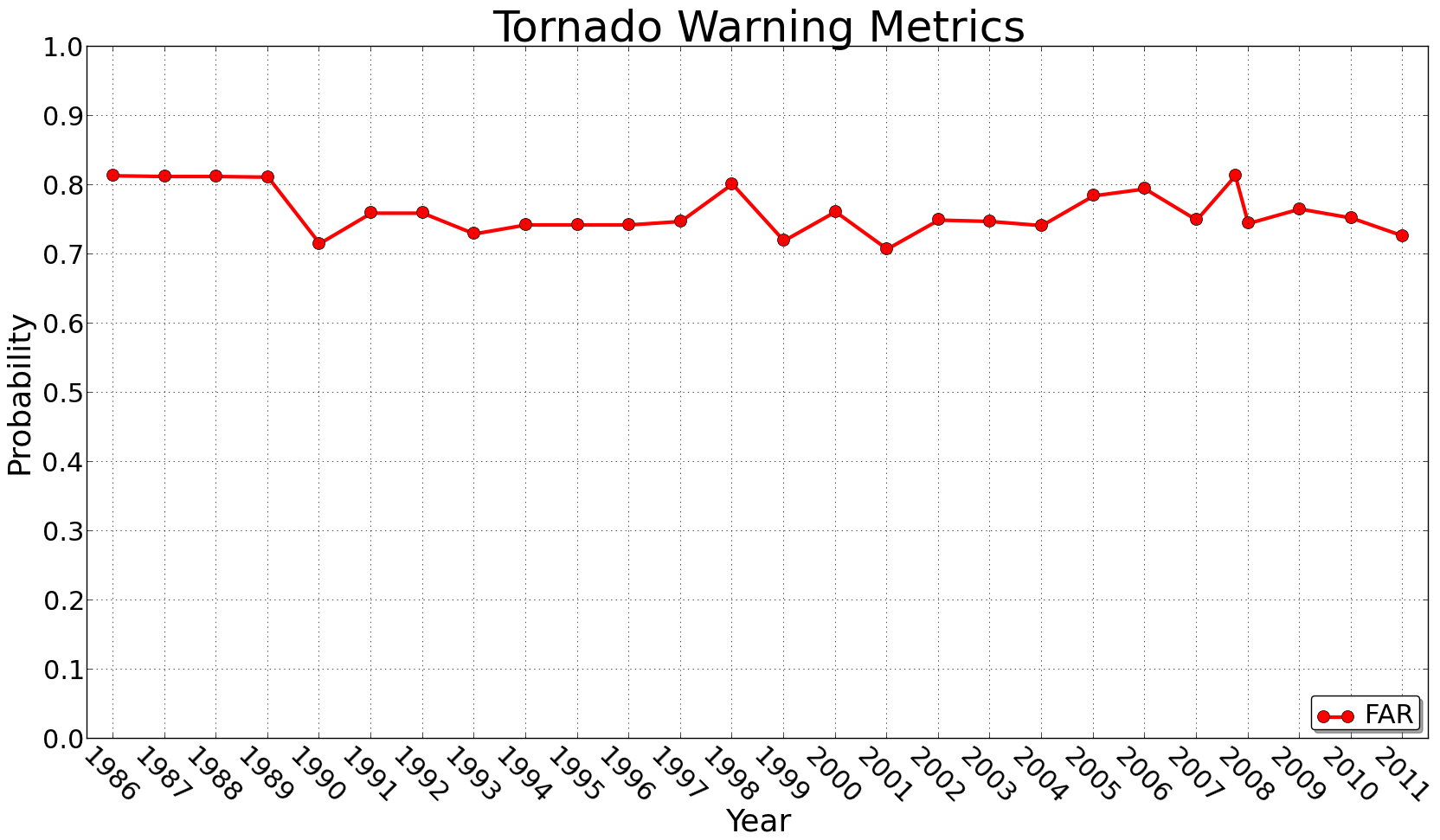

Maybe chasers have an impact on the False Alarm Ratio, or the number of times a tornado warning is issued and a tornado fails to develop. Certainly chasers have had an impact here, right? After all, with the number of chasers out there reporting what the see in real time back to the NWS, the NWS is issues fewer tornado warnings where no tornado occurs. Unfortunately, as the figure below indicates, the False Alarm Ratio, or FAR, has not changed since 1986. It has remained fairly constant around 75%

Yes, I admit that all of this “evidence” is circumstantial; maybe the improvements since 1990 are the result of chasers and not Doppler Radar. (Maybe we should ask NWS forecasters if they would rather have Doppler Radar or chasers?) I also admit that there could be some chasers who really do chase with intention of “saving lives” or “aiding the warning process”, but I think these chasers are few and far between. Instead, what I really see, and believe, are chasers who are interested in chasing for their own reasons (adrenaline, fame, money, etc) and try to pass it off as a noble cause. If people really did chase for the sole reason of helping others, there would be no need for still and video cameras and no need for chasers to get as close as possible. Please don’t insult my intelligence by claiming to chase to “save lives”. I do not see paramedics and firefighters setting up tripods at the scenes of fires and accidents, so why are chasers unless there is another motivation? At least be honest with yourselves and with those around you, and say you, and most other chasers, chase for personal reasons, and if you remember to help the NWS out while doing it, you try to do so.

To summarize, I believe chasers have a limited impact on the warning process, and don’t appear to directly “save lives”. With that said, I don’t have no problem with people who want to chase. My problem lies with people who chase and then are dishonest about, or at least misrepresenting, their intentions.

Lastly, I want to make a distinction between “spotters” and “chasers”. Spotters have been around for a long time, dating back to the days of World War II (and possibly longer). The role of spotters used to be to warn military bases about approaching thunderstorms so that people could be removed from munition depots on the off-chance that lighting stuck the munitions. Spotters tend to be tied to local communities and have relationships with the local officials involved in decision making process. I suspect that spotters have a much greater role in the warning process than chasers, although, it appears (at least circumstantially) that this contribution is still at the margins.

Again, these are my interpretations of the data; I’m sure others will interpret the data in other ways, and I have no doubt that those of you who disagree with my interpretation will let me know.